READING added on October 1, 2022

May 21, 2022

A small agile man harnessed all four mules in the dawn light best to get going early. A close mucky night made even the skeeters lazy. In the night without the sun the heat was less intense, but it clung more. As the sun rose heat waves began shimmering. The hot of the day rising higher with the sun. Looking to the horizon blurred the vision for even a sharp-eyed man. A translucent curtain woven in July’s oven. The sun was a forager taking back the last rain, the spring rains, and the winter snows. As he headed to the corn field the wiry man thought the earth and every living thing was about sweat out. He could leave two mules in the shade up by the spring fed slew. Switching off letting one pair rest and cool down would allow him the long day needed. The corn could be laid-by before night if he kept steady walking behind the cultivator. Row after row all day gradually closer to being done. The last rows ending up by the crick itself. Slight puffs with each step, the dirt holding more heat as he made each round.

Most of their farm was bottom ground less than a third in second bottom. The mules, the shovels, and his own steps raised a fine dusty mist. A miller’s dusting settled accumulating coating hat, hair, skin, and clothes, even the mules were a lighter shade. After today the bottom would be done until Fall. All any man could do would be done. Time to let the corn tassel and shoot then see what ears it growed. As hard as the steam bath of the bottom was on men and mules, the corn relished it. One good year in the bottom was worth three in the hills, but it had already been three years since that good year. Never dried out last year until too late. If past Independence Day stay away. Got half of it the year before that and not even an ear the year afore that one. Corn looked so green and full today, even the heat wasn’t rolling it too bad. The roots were strong reaching down into good moisture.

Family had been working this bottom for some time. Pa and old Levi spent winters chopping the big timber. Levi Salisbury would pole up the crick making it by late Fall. Ma would winter him, and he would help Pa chopping trees. They swung axes each stroke on mark periodically resting by changing sides switching from a left-handed swing to a right-handed. Each one steady whether left-handed or right-handed striking with axe, a swing back and then a swing down to strike again. Steady a way to get a tree cut down, many trees winter after winter. All the family worked keeping the crick from cutting new paths across the open fields. Yes, we had earned this bottom, now called Whiteman’s Bottom.

The young man had always been good with animals especially horses and mules. Handling his team with command even when well shy of being a teenager. The tallness of his father never reached him; he had followed after his mother’s family of short people. He carried a drive and push larger than his height. He knew when to stop pushing a team. He knew his animals. He had broken an eighty out of prairie. He was given landlord’s share for five years for every acre he plowed. It had taken several years. The saw grass so sharp he wrapped the mules’ legs with burlap and designed a leather apron to protect their chests. The grass would slice mule flesh like a knife without the coverings. Oil wells had gone in over by Colmar. He had made good money dragging casing pipes with his mule team. The drillers had tried to talk him into taking his team to Kansas where they were moving on to. Farming was what he wanted not being a teamster, but he did like his teams.

He was approaching the bend in the crick. It would be time to trade teams when he finished this round. The bend always brought back fishing memories. His family was always hunt’n or fish’n when not farm’n. This time a memory of that steam car popped in his mind as he turned and dropped his shovels back in the rich dirt. The old man would drive out and find him when he was a boy. They would go down to the crick to fish. He had learned all about cars and was often a local mechanic. He remembered keeping that little warmer burning to get the car going when they were done. The old man had offered him the sod buster deal. It had worked out, but he and his mules had earned it.

He switched out teams. He dipped out some spring water and quickly devoured cornbread he had brought along. Time to get back to the monotonous down and back. The shimmering at the end of the bottom looked like a wall or an apparition. Once you reached it, it disappeared. This pair worked well seemed to be adjusting to the heat. Maybe they would have liked Kansas over this bottom. Weather would be cold by the time he and his long-eared partners were back working this field. Skeeters would be gone by corn picking time. At least in the heat of the day they were not out.

He had strong hands and wrists. He was quick and nimble with his hands it made him a skilled corn shucker, a hundred-twenty-bushel man. He would enjoy working on the family farm not up north in Uncle Will’s field or one of Will’s neighbors. Always lots of good corn to pick up there in the rolling prairie. No cricks to take away a year’s work. The second bottom had only twenty to thirty acres. Crick never got there at least not in anyone’s memory. Enough to get you by and feed the animals. Prices were up because of Europe. Times seemed promising if there was a crop to sell. Uncle Grover might have to haul his own sorghum. Hauling a load of sorghum to sell and then having his wagon to pick in had gotten folks by. The mules plodded along, and he did as well. Sun had moved past its high mark; it seemed to standstill. Hot and still the corn was tall would shade in soon. Focus on each step he needed to finish.

He was past the bend; the rows would be shorter now. There was a reason this crick was called crooked. He had been at it almost twelve hours now, being done was closer. He would give extra care to the hard-working mules. He would then eat a great supper. Ma always fixed great meals with the garden stuff she would have picked this morning. Tonight, he would be sound asleep even if the skeeters came out. A little breeze during the night would be a comfort. He could hope for that. As the day was close to an end, he looked across the field back over all that was done. Across the shimmering bottom the field looked lush in spite of the heat. He turned and lined up only three rounds of short rows left.

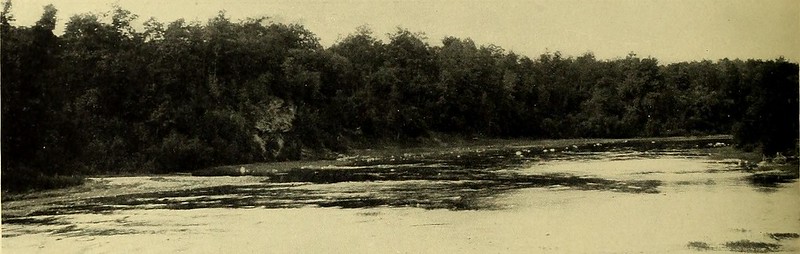

A glint, a reflection what was that? The mules looked back with some doubt questioning why he had pulled them up. He tied the mules by some trees on the border of the field. They welcomed the shade even if they were ready to finish. He looked down in the swale, something rippled. He walked up to a higher spot. He could see the crick from it. The string of cuss words he uttered would have been impressive if anyone had been there to hear it. It was surprising one small man could have stored so many. The crick was coming out of its banks. The water was raging and swirling carrying debris and menace. The water was just beginning to flow across the field. At first like a field being flood irrigated. He could see it rising the crick was jumping fast. Here there had been no rain not even thunder but upstream on one branch or the other or maybe both, a gully washer had been unleashed. A source of transit, food, fun, and beauty, but when it turned it was wild. The crick was bipolar. It was demonstrating its rage now. Mindlessly seeking to destroy anything or anyone. The mules needed care he got them together and headed home. He walked behind silently filled with white cold anger. The crick had lost its mind, now it would rage down its course. When hard work, the pushing, and driving all came to naught reality struck home. No human power could overcome the crick. One’s efforts, even those willing to work beyond most men’s limits, were pushed aside as the bully ruled the day.

He cared for his mules patting speaking softly praising them for a good day. He hung the harness up with more force white-hot anger expressing life’s futility. He then walked out to the pasture gate. From here he had a view of most of the bottom. On the higher spots the green leaves still visible. Most of it looked like a turbulent lake, a home for the catfish and buffalo, not corn. He stood silently watching a year’s work washed away in an hour. A tall lanky man came home from working on the threshing run. His short wife came out spoke softly to him pointing to their son leaning on the gate. His son stood still motionless staring out across the bottom. He nodded and slowly walked over to stand beside him. They stood in silence for a spell.

The young man said, “I ain’t going back in that bottom. Not putting a plow or another dollar into it. Many farms up north where the crick doesn’t come rob you.”

His father replied, “It is a hard thing today.”

“I was just about to finish the last round and there it came trickling across the low spot. Must have been a big storm from the looks of the current. It was rising fast. Uncle Will may know of a place to ask about.”

“Your Uncle R may know of some place around Franklin, he’s on the bank board. Alfred says Franklin has a big future. Land is good up there, but farming is a tough road anywhere.”

“Yes, but don’t have the devil of that crick.”

“Yep, our family been here in the hills and on the crick near a hundred years. Fever took our youngest and the older kids out on their own now. If you are pulling out maybe we should go, we’ll talk it over at supper. I know it’s hard. Let’s wash up and then talk tonight.”

“Think Ma will want to move and start over?”

“Her folks moved up to Franklin, now most of her brothers and sisters are up there. I’ll pump out some water. We’ll all think better after we’ve et.” The family found farms and left. They never put another crop in Whiteman’s bottom. Eventually all the Whiteman’s left. Locals hearing the name Whiteman’s Bend and Whiteman’s Bottom but not knowing any of the ones who gave their name to it. Old Crooked Creek had won.

Farming has many threats, many disasters besides floods. Hard work won’t overcome bad timing. Old farmers know the hard times can come quickly as a thunderstorm. Farmers pay what they ask and take what they are offered. Farmers live tight to survive. Sometimes work, frugality, and skill fails, then it all comes to nothing.